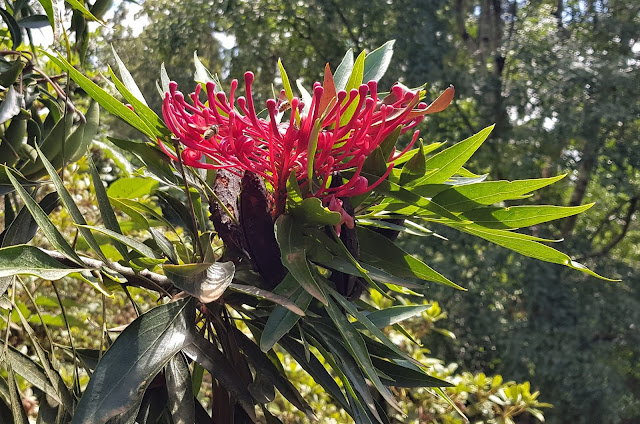

Dorrigo Waratah's late flowering worth the wait

|

| Dorrigo Waratah |

Oreocallis was a name devised by the English botanist Robert Brown (often tagged 'the father of Australian botany' in recognition of his discoveries here between 1802 and 1805), meaning 'mountain beauty'. Leading up to the study by Drs Weston and Crisp, the genus extended from Australia to New Guinea, then across to Peru and Ecuador. Post-1991, the South American duo remained in Oreocallis.

(Some of these species began life in the genus Embothrium, a name published in 1776 by Johann Forster and his son George, who joined James Cook on his second voyage to the Pacific. That genus now includes only a single species, Embothrium coccineum, the Chilean Firetree, from Chile.)

|

| Dorrigo Waratah |

Weston and Crisp's decision to pull these species out of Oreocallis was supported by distinctive features such as wood anatomy, but considered necessary when they found that to maintain the integrity of the classification system (that is, to reflect likely relationships and evolution) they either had to 'sink' Telopea (Waratah) into Oreocallis, or pull out what they called Alloxylon.

And so we have this beautiful Australasian genus, Alloxyllon (not to be confused with another closely related red-flowering Proteaceae tree, Stenocarpus sinuatus, the Queensland Firewheel Tree, which has flowers arranged in a distinctive flate 'wheel').

Most often in botanic gardens and parks you see, or at least I see, Alloxylon flammeum, the Queensland Tree Waratah. This rare tree from remnant rainforest near Atherton is popular with specialist growers. Here is is growing and flowering in Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney in September (2009), then close up in Brisbane Botanic Gardens in August (2019).

|

| Queensland Tree Waratah |

|

| Queensland Tree Waratah |

The other Australian species, Alloxylon wickhamii, the Pink Silky Oak (or Pink Tree Waratah) grows near to Alloxylon flammeum in far north Queensland but extends further north into Cape Tribulation. Neatly, it flowers in between the other two Australian species, from October to November!

All species are striking when in flower, with their 'fire'-like blooms. In addition to the late summer flowering, the Dorrigo Waratah can be distinguished by the mostly divided (pinnate) leaves. Young leaves of the Queensland Waratah can be divided but not right through to the midvein, and they are little blunter than the 'spear-shaped' leaves of the Dorrigo Warratah.

|

| Dorrigo Waratah |

Also, if you count the number of flowers in each flowerhead you'll also notice there are up to 140 in the Dorrigo Waratah and always more than 50, the maximum for the Queensland Waratah.

So for big bold blooms in later summer, it makes sense to go with the Dorrigo option. However ... a bit like the true Waratah (Telopea), this species can be difficult to grow in cultivation. That said, the two specimens I saw in Dandenong Ranges Botanic Garden looked to be in great health, and I know it's grown in Australian National Botanic Gardens in Canberra and the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden in Mount Tomah.

The Queensland Waratah is hardier, and it is the species we favour in the Australian Garden at Cranbourne Gardens. In Melbourne Gardens, we have one Dorrigo Waratah and one Pink Silky Oak. So, happily, if you flitter between the two Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria sites you can enjoy Alloxylon flowers for about six months of the year. In theory.

Comments

Any ideas where I can get a Dorrigo Waratah seedling or cutting? I have not found a single nursery that sells them.

Pete