Codex reveals lanky Mexican succulent

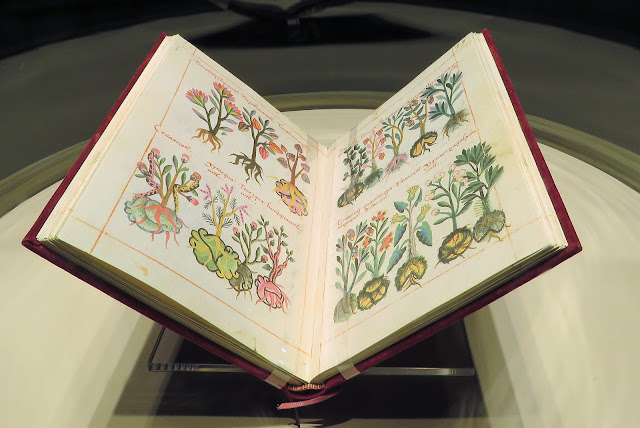

One of the earliest books to document the medicinal properties of the Mexican flora was The Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, The Book of Indigenous Medicinal Herbs. It is better known as the La Cruz-Badiano Codex, written (in the Aztec language, Náhuatl) by Martin de la Cruz in 1552, and translated in Latin by Juan Badiano.

While it and its relatives (including many cultivars and hybrids with Echeveria gibbiflora as a parent) may suffer from being too familiar, there is still potential to do something interesting in their display, as here in another Mexico City botanic garden, near Grasshopper Hill. Homely perhaps but clever.

The original is held in the Vatican Library but I saw this copy of the Codex in the La Flor en la Cultura Mexicana exhibition at Mexico City's Museo Nacional de Antropología, which I featured a few posts ago. In that volume, the account of Echeveria gibbiflora includes the Náhuatl name Tememetla, as you can see here in a page photographed by my friend Manuel Bonilla Rodríguez followed by a paragraph more recent published guide to the Codex.

The Codex reports on this species being used for swelling of the mouth, diarrhea and pimples. All of which it occurs to me might result from eating too much Mexican chicolatl. Cacao gets a passing mention in this Codex but becomes a cultural motif in the later (1577) Florentine Codex.

I don't know what Tememetla means but the English common names Donkey Ear and Cow Tongue are pretty self explanatory. The scientific name is partly (Echeveria) in honour of the late-eighteenth century Mexican botanical artist, Atanasio Echeverría y Godoy, and the rest (gibbiflora) a description of its 'humped flowers'.

I don't know what Tememetla means but the English common names Donkey Ear and Cow Tongue are pretty self explanatory. The scientific name is partly (Echeveria) in honour of the late-eighteenth century Mexican botanical artist, Atanasio Echeverría y Godoy, and the rest (gibbiflora) a description of its 'humped flowers'.

Echeveria gibbiflora lives in relatively high altitude areas among drought tolerant shrubs, exactly like the lava flow ecosystem near the Mexico City university Manuel studies in his post-graduate ecology degree. Here are some pictures of the species in habitat, largely hidden at this time of year among dry grasses, although you can see the flowering stems emerging up to a metre or two high.

In the nearby botanic garden (below) you can see the plants in more detail. Echeveria gibbiflora is the largest of the 150 or so species of Echeveria, although this genus will one day be dived further on the basis of recently DNA studies.

This succulent is never particularly elegant and certainly not compact, but it does have a certain lanky swagger about it.

Comments

(E)Stuart(o)