Blood red algal blooms inspire budding artists

The offending alga turned out to be a dinoflagellate called Noctiluca scintillans, also known as the sea sparkle as if to counter the macabre headlines. In fact this species is equally well know for its bioluminescence, which is worth a post in itself (I've mentioned bioluminescent fungi, and wrote a feature article on this topic for Nature Australia back in 2003 but it is sadly not on-line).

Algae often (although seldom from this extremely biased writer) get a bad rap. Red tides particularly are unsettling, kill marine life, and can cause skin irritations and worse in humans. But like much in the environment - good and bad - red tides (and algae) are frequently misunderstood.

The Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida, have come up with a new way to address this communication problem. They have created art to tell people all about red tides. The project is called The art of red tide science, and it even has its own Facebook page.

The project was created in response to Florida residents and visitors having 'misconceptions about even the basics of Florida red tide' after 20 years of advancing scientific knowledge by the local researchers. Their problem alga is Karenia brevis, also a dinoflagellate and also responsible for blood red tides.

The project was created in response to Florida residents and visitors having 'misconceptions about even the basics of Florida red tide' after 20 years of advancing scientific knowledge by the local researchers. Their problem alga is Karenia brevis, also a dinoflagellate and also responsible for blood red tides.

It seems the alga is not all bad. A compound produced by Karenia brevis can actually act to block the more toxic chemicals produced by the same species, and it has potential as a treatment for cystic fibrosis. So this is part of the communication message - algae can be good.

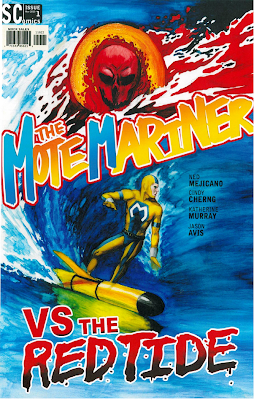

The approach they took was to ask students at the Ringling College of Art and Design to work on 15 different ways to portray red tides in art. The maximum budget available for each project was US$200. I've included here three of the results illustrated in the paper cited above (The art of red tide science).

One thing that came out of the project was that 'art students are far more creative than scientists when producing outreach materials'. And previous studies had shown that works created by graphic artists but based on text provided by scientists were described as '100% accurate but too detailed and not "eye catching"'. None of the art students have any formal scientific background so they relied on information provided to them by local researchers, as well as that ever reliable source, the internet.

Emily Hall, Kate Nierenberg and the other authors of the paper note that contrary to popular opinion, most learning about science is from 'media, museums and interpersonal contacts', rather than through formal schooling. That said, visitors to the Mote Marine Aquarium (where the art works were displayed) voted a video game - assessed as having 'very little scientific information content but high entertainment value' - as their favourite.

So we might learn science from art, but slowly.

So we might learn science from art, but slowly.

Images: the art images (including the top picture) are from the journal article by Emily Hall and colleagues. The microscope image is from micro*scope - it's a cell in the Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton, and taken by David Patterson and Bob Andersen. The Bondi Beach shots are from msn and The Times on-line.

Comments

yeezy boost 350 v2

nike sneakers for men

jordan shoes

louboutin outlet

nike air max

nike air max

yeezy boost 350

off white jordan 1

curry 6